THE CHURCH

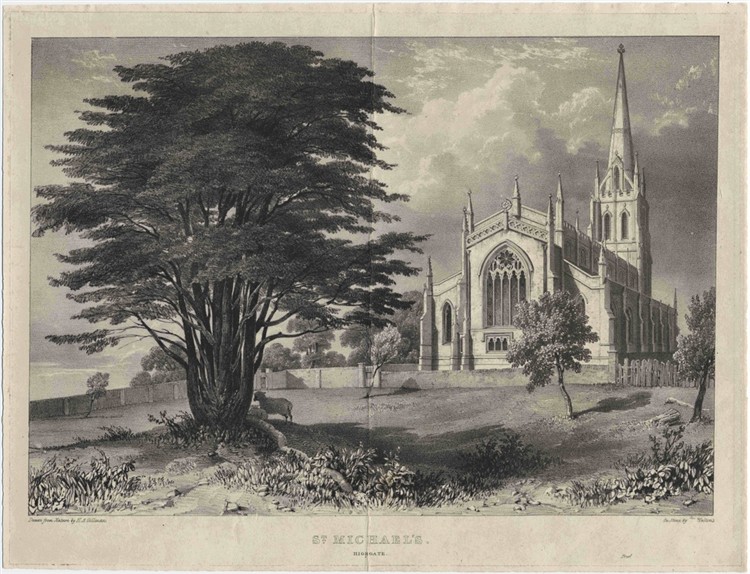

St. Michael’s, Highgate stands higher than any other church in London. As you enter you are all but level with the cross on top of St. Paul’s Cathedral. It is not an ancient church. It was consecrated and opened for worship on 8th November 1832. The Architect was Lewis Vulliamy (1791-1871). He was quite a young man whose drawings for the church were exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1831. The design was considered to be an outstanding example of the neo-Gothic style, of which the Architect was a pioneer. It was said of him that he was “far in advance of his contemporaries at a period when Gothic was but little known”.

The builders were William and Lewis Cubitt who completed the construction in eleven months.

THE HERMITAGE CHAPEL (1100-1564)

In ancient times the hamlet of Highgate lay partly in each of the parishes of Hornsey, Islington and St. Pancras, the churches of which were more than two miles away. When the Bishop of London was given the Manor of Haringey by William the Conqueror, he reserved the southern part of the estate as a hunting-park and settled men in it as huntsmen and foresters. He also gave some eight acres at the very top of the hill for a hermitage and a small chapel; records suggest that the provision was for just one hermit.

In 1539 the hermitage and chapel were closed down as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and the land disposed of. Sir Roger Cholmeley gained possession of it and in 1565 was granted letters patent by Queen Elizabeth to set up there his Free Grammar School. Sadly, he died that same year and it was the trustees who established the school in his name. From 1576 a school chapel was built.

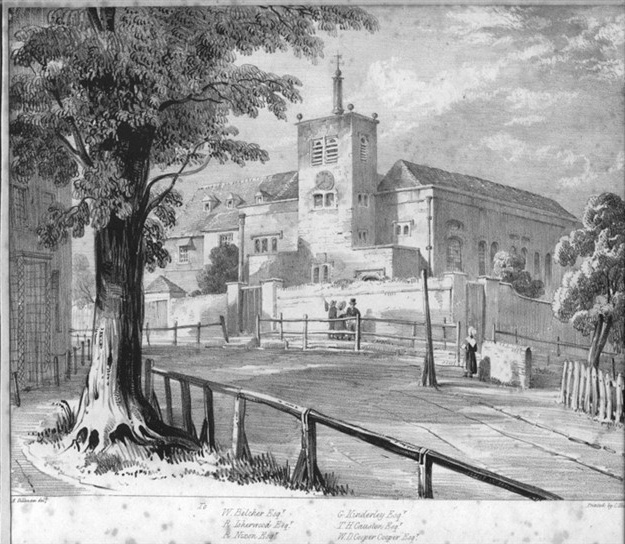

THE SCHOOL CHAPEL (1576-1832)

The school chapel was a substantial brick building with a square tower also of brick, though it had a timber roof supported on oak columns. It was enlarged a number of times and, there being no church, it was a place of worship for local people as well as for the school. For 250 years it sufficed to serve the whole community, but early in the 19th century extensive repair was necessary and considerable enlargement was required to hold the growing population.

By 1820 there were but a few pupils at the school and the headmaster focused his attention more on the chapel and the local people than on schoolmastering. In 1822 a bill was put before Parliament to empower the school governors to pull down the chapel and build a new one to meet the needs of the locality.

The proposal was met by forceful opposition. This would be, it was claimed, a misuse of charitable funds. The Times, in a leading article, thundered against this measure and the bill was thrown out. The dispute ran for many years. Court proceedings were taken and eventually the Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon, gave judgment that the chapel and its burial ground did in fact belong to the school, and a new church should be built elsewhere in the village.

THE CHURCH BUILDING ACTS

In 1818 an Act of Parliament was effected, being An Act for the Building and the Promotion of Building Additional Churches in Populous Parishes. Under this Act and its subsequent amending Acts, 600 new churches were built in different parts of the country. St Michael’s was one of these. The Commissioners for the Building of Churches (a body set up under the Act) were the client in the construction contract. An Act of Parliament of 17 June 1830, pursuant to Lord Eldon’s judgment, allowed the governors of Cholmeley’s school to contribute to the cost.

As mentioned above, the church was completed in the remarkably short time of eleven months, but then stood empty and unused for nine months. It could not be consecrated because it did not meet the requirements of the Act under which it was built – because it was not situated within the diocese of London. The land on which it was built was from the parish of St Pancras, which was a peculiar under the jurisdiction of the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral. A further Act of Parliament was passed to overcome this problem.

VULLIAMY’S CHURCH

The site chosen for the church was the semi-derelict Ashhurst House which had been the seat of Sir William Ashhurst, who had been Lord Mayor of London in 1694. The house was demolished in 1830; its bricks may still be seen in the crypt together with the remains of the wine cellar. As you approach the church you might notice that the corbels of the arch over the West door are carved to show coats of arms. These, though weathered, are the arms of Bishop Edmund Grindal and of Sir Roger Cholmeley.

The cost of the new church was £8,171; in other words it was built as economically as possible. The cost of construction per seat was £5.25. A similar church by the Architect in Kensington was £8.30 per seat. The Commissioners for the Building of Churches contributed £4,811, the Incorporated Society for Church Building provided £500. The Governors of the School contributed £2,000 which they raised from the sale for development of some of the land that had been used as a burial ground. The remainder was raised by subscriptions from the parishioners. In return for the contribution from the School the Governors and the boys of the school had seats reserved for them in the new church. The school built their own new chapel in 1868.

THE EXTERIOR

The spire, which is a landmark on the northern skyline from the hills south of London, gives a grace and dignity to the whole frontal elevation. It is of Bath stone surmounted by a cross of Portland stone. The upper portion has been rebuilt three times, twice following lightning strikes and the third time after damage from enemy action in the Second World War. “The church with the slender spire” in Highgate is mentioned by Dickens in David Copperfield.

As is usual in English churches, the nave is considerably more lofty than the side aisles. The main roof (carried on timber trusses) is supported on clerestory walls borne on internal pillars; the two separate side-aisle roofs are supported by cast iron girders. It should be added, that the clock, with a very fine copper face, and the tower bell were given early in the 19th century by an ironmaster, George Crayshaw who lived on Highgate Hill.

THE INTERIOR

Inside the church as you stand at the back you see the original design as modified by alterations made since 1832. The original building seated 1527 people. There were 553 free seats, some seats for school and governors and 934 seats to let, the rents from which would pay for the Vicar’s stipend and certain expenses. The number of seats has since been considerably reduced by the creation of the present chancel and south chapel, and by taking away some pews both from the front and the back of the church.

Originally St Michael’s was fitted with closed box pews, and there were two walkways within the nave. At the back of the church (the west end) and to your left as you face the altar, there is a model of the church (in a glass case) and, close by, there are framed prints of both the exterior elevation and interior of the church all as it was in 1832. In a reordering of 1879, the present open benches were introduced, with just one central walkway – and at the same time the heating system was installed.

In 1880 the church was extended eastwards by one bay, the architect being the famous George Edmund Street. He formed the new east wall and window and created the chancel.

The pulpit was installed in 1848. It was set quite high to enable the preacher to speak directly to the occupants of the gallery as well as to those in any other part of the church. In the eighteen thirties when the church was built the sacrament of the word was deeply cherished, but towards the end of the nineteenth century the importance of music and ritual came to be more and more widely appreciated. This was no doubt partly a result of the influence of the Oxford Movement, an influence which extended to parishes throughout England and not least to urban churches which would have called themselves strongly Evangelical. Thus when St. Michael’s was first in use there was no robed choir, and the choir were seated in the west gallery. Choir practices did not begin until 1865.

A good provision for the choir did not come until the church was extended by one bay in 1880-81. The creation of the chancel, with stalls for the choir, changed the church greatly. The architect for this project, as for the reordering of 1879 was the famous George Edmund Street, designer of the nave of Bristol Cathedral and of the Royal Law Courts in the Strand.

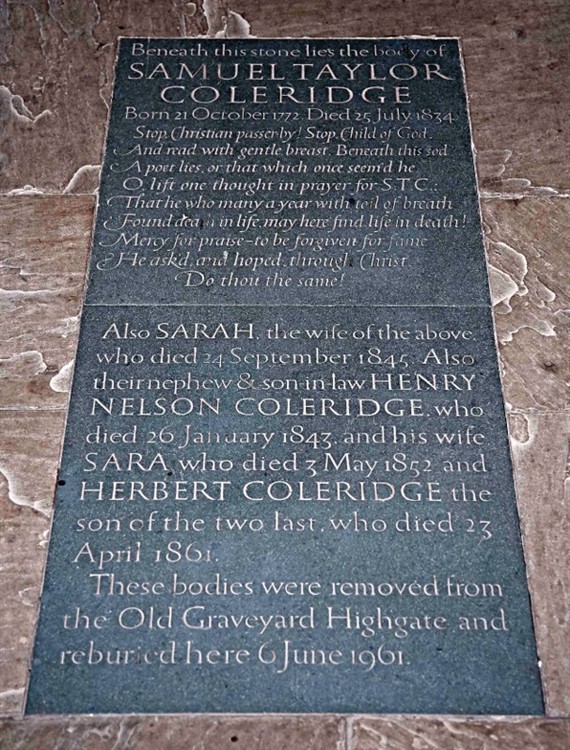

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

Chief of all the monuments in the church is the slate slab in the central aisle in memory of Coleridge, his wife, and their daughter with her husband (Coleridge’s nephew) and her son. It has on it memorial words written by Coleridge himself when he knew he was dying. The original grave of Coleridge was in the burial ground at the top of the High Street, but when the new school chapel was built in 1868 it overhung the Coleridge vault which then became neglected. A fund, much of it from the United States of America, was raised by an English novelist, Ernest Raymond and on 6th June 1961 Coleridge’s remains were reburied in the crypt of St. Michael’s. The Poet Laureate, John Masefield, gave the address at the unveiling of the stone.

Coleridge certainly worshiped in the church in the eighteen months that elapsed between the consecration and his death.

To your left (on the north wall) there is an additional memorial to Coleridge and to Dr. James Gillman and his wife with whom Coleridge lived in Highgate for the last nineteen years of his life.

THE EAST WINDOW

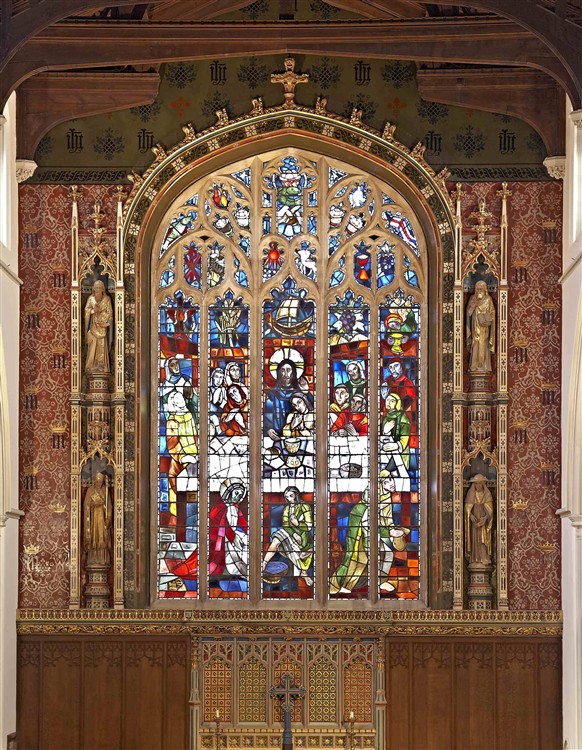

The eye of the visitor today will be lifted first to the great east window with its modern adaptation of the finest medieval stained glass and to the decorative colouring of the Chancel wall each side.

An East window was in the original design, although there was no Chancel, only the Sanctuary. The first window represented the Entombment and the Ascension and was given by the assistant minister of the old chapel. The reordering by Street created a larger window in the Perpendicular style, initially filled with clear glass. In 1889 a Tree of the Cross window, by Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1927), a noted stained glass artist, was installed. In 1944 a flying bomb in Waterlow Park shattered this window; some rescued fragments were re-erected in the north aisle window.

The present East window, from 1954, is one of the last achievements of Evie Hone (1894-1955). It represents the Last Supper, the washing of Peter’s feet and the creeping away of Judas with his money bag. Above in the tracery of the window are numerous symbols of the passion and of the Christian church. The visitor will find these described on the table at the back of the church. Miss Hone, whose studio was in Dublin, had but a few commissions in England, the most notable of which was the east window in Eton College Chapel. The St Michael’s glass was sent by air from Dublin and erected under the supervision of Mr A. P. Robinson, the Church Architect, by builders Dove Brothers. Miss Hone died soon afterwards and never saw it installed.

THE EAST WALL AND SANCTUARY

The decoration of the East wall in 1903 was the work of Temple Moore (1856-1920), a pupil and associate of George Gilbert Scott. Moore was the third eminent Gothic Revival architect to contribute to St Michael’s as we know it today. The wall colouring and the retable with its cross, and the four carved figures of Saints of the early Church make a frame enhancing the splendour of the sunlit window. The Saints are Athanasius (signifying the Faith), Augustine of Hippo (care of the poor), Chrysostom (preaching), and Jerome (the translator of the Bible). In 2011 this wall decoration was cleaned and restored by means of a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. See The East Wall Project.

In the Sanctuary is the Episcopal Seat from the firm of the famous wood-carver Thompson of Kilburn, Yorkshire, whose personal mark was to feature a carved mouse on each piece of furniture.

In the choir you will find a fine set of cushions. These together with the Altar frontals and all the other embroidered work were designed by Miss Sylvia Green and stitched by members of the parish.

THE SOUTH CHAPEL

In the chapel on the South side, the window (1906) by Charles Kempe shows St. Michael slaying the wyvern. The fine oak screen separating the chapel from the choir was designed by Arthur D Sharp and erected in 1905. The west screen and the reredos were by Temple Moore in 1906. The majority of the memorial plates are in memory of those killed in the Great War (1914-1918), the parish War Memorial being at the entrance to the chapel.

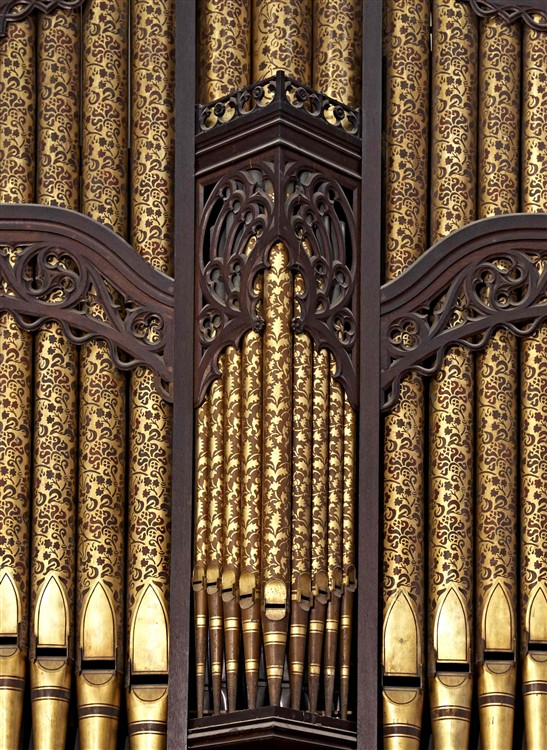

THE ORGAN

An organ was first built, in the west gallery, in 1842 by Messrs. Gray & Davidson at a cost of £700. It was paid for mainly by a double pew rent for one year. In 1859 it was cleaned and lowered to a new position in the gallery. Again in 1873 the instrument was cleaned and modernised.

After the enlargement of the church in 1881, the introduction at the east end of a surpliced choir, with 18 boys in addition to the men, accentuated the distance between organ, choir and congregation. A report, circulated to all parishioners in 1883, recommended a new, or almost new organ, in the east end behind the choir. In 1885, Hill and Davidson provided such an organ.

In 1911, following the complete breakdown of the organ on several occasions, Messrs. Brindley & Foster were contracted to rebuild and enlarge the instrument. In 1958 a further rebuild was undertaken by the firm Rest Cartwright which included a detached console on the north side of the Altar with the player facing west.

By 1977 the organ was a sad and dim reflection of its former character. Thus in 1985 the decision was made for a comprehensive rebuild incorporating the best of the old pipe work into the organ you see now. The builders Nicholson of Malvern by careful design were able to contain the organ within one bay. The organ contains 58 drawstops and 2523 pipes. Detailed specifications and the history of the organ are contained in a pamphlet at the west end of the church. The instrument was cleaned, and slightly enhanced, in 2011.

THE MEMORIALS

The “Steinway” grand pianoforte was a gift of the parishioners to commemorate three young sisters who had many friends in Highgate. They were daughters of a former Curate of the Parish from 1985 to 1988. The children were pupils at the parish school and members of the choir. The girls died in their sleep as a result of fumes from a fire which destroyed Chilmark Vicarage, Wiltshire.

At the West end of the church you will find a number of 18th century memorials from the old chapel. The most noteworthy is above the west gallery, the memorial to John Schoppens (1720), a wealthy Dutch merchant who was naturalised by Act of Parliament of Charles II. His daughter married a John Edwards and they lived in Ashhurst House, the site of which was to become the site of St. Michael’s Church. John Edwards (his son having pre-deceased him) left Ashhurst House to his grandchildren who joined with their children to sell the site to the Church Building Commissioners in 1830. A memorial (1761) to John Edwards and his wife is in the tower room over the porch of the church.

Under the gallery on the South and on the West walls are other memorials removed from the old chapel: Sir Edward Gould who endowed the almshouses; Rebecca Pauncefort wife of the man who built them and Samuel Forster; but these have antiquarian interest only. Some monuments of later date than 1832 are especially noteworthy. They include inscribed memorials to George Kinderley, the barrister who succeeded in getting St. Michael’s built, to Dr. James Gillman, who took Coleridge into his care and to Coleridge, written by Gillman.

There is a book on the table at the back of the church listing all the memorials and their locations in the church.

THE ADJOINING PARISH ROOMS

During the early 1980’s the Parochial Church Council and the congregation of St. Michael’s Church felt the great need to provide a new Church Hall adjacent to the Church itself. This was necessary for the broader social and educational aspects of Parish life.

Having looked at the various options including the use of the area under the Church itself the decision in 1985 was to build on the North side of the Church. The finances were raised through the selling of the old Church hall next to St. Michael’s school and by a wide appeal to the congregation and residents of Highgate.

Melville Poole the Architect was chosen to design and supervise the building of the new centre, which was completed in 1988. This building has added greatly to the life of St. Michael’s Church. Knowing the needlework skills in Highgate, the Architect anticipated that the high brick wall of the staircase would be the right place for an embroidery to bring warmth and contrasting colour and texture to the building. Sylvia Green and the St. Michael’s Embroidery Group decided that the embroidered panel should depict the Church surrounded by characteristic buildings in the village and by such landmarks as Highgate Cemetery and Kenwood House. The outlook from the upper room to the South is over the catacombs of Highgate West Cemetery towards the City of London.

It is sad to relate that Melville Poole died within a few months of the completion of the work. His name and the names of all those who worked on the building are recorded in a mural plaque by the entrance of the new extension.

EXTERIOR FLOODLIGHTING

The site chosen for the Church, although higher than that of any other church in London, has one major disadvantage. Because the Church was set well back from South Grove it was, after dark, obscure and hardly noticeable.

An appeal to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II by floodlighting the tower, steeple and west end was launched n 2002. The congregation, the Church’s neighbours and many associated with Highgate responded generously to the appeal and £25000 was raised. The work was completed in the summer of 2003 and the lighting formally switched on after choral Evensong at the patronal festival on 28th September 2003.

THE REORDERING IN 2011

Extensive work was done to the interior of the church in the early months of 2011. In addition to the restoration of the east wall, the whole building was redecorated. At the same time, two further rows of pews were removed at the back of the church, the west end paving was completed and new facilities were built. These comprise a kitchen servery on the north side and a matching flower room/book store on the south.

VISITING THE CHURCH

You can visit St Michael’s and see for yourself the things described in this brief history. You are of course most welcome to any of our services, or to make arrangements for a group visit, please contact the office for more details. When visiting you will be able to enjoy our two guidebooks, one on the east wall and one for the church as a whole, at no charge.